Food insecurity adversely affects human health, which means food security and nutrition are crucial to improving people’s health outcomes. Both food insecurity and health outcomes are the policy and agenda of the 2030 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). However, there is a lack of macro-level empirical studies (Macro-level study means studies at the broadest level using variables that represent a given country or the whole population of a country or economy as a whole. For example, if the urban population (% of the total population) of XYZ country is 30%, it is used as a proxy variable to represent represent country's urbanization level. Empirical study implies studies that employ the econometrics method, which is the application of math and statistics.) concerning the relationship between food insecurity and health outcomes in sub-Saharan African (SSA) countries though the region is highly affected by food insecurity and its related health problems. Therefore, this study aims to examine the impact of food insecurity on life expectancy and infant mortality in SSA countries.

The study was conducted for the whole population of 31 sampled SSA countries selected based on data availability. The study uses secondary data collected online from the databases of the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), the Food and Agricultural Organization (FAO), and the World Bank (WB). The study uses yearly balanced data from 2001 to 2018. This study employs a multicountry panel data analysis and several estimation techniques; it employs Driscoll-Kraay standard errors (DKSE), a generalized method of momentum (GMM), fixed effects (FE), and the Granger causality test.

A 1% increment in people’s prevalence for undernourishment reduces their life expectancy by 0.00348 percentage points (PPs). However, life expectancy rises by 0.00317 PPs with every 1% increase in average dietary energy supply. A 1% rise in the prevalence of undernourishment increases infant mortality by 0.0119 PPs. However, a 1% increment in average dietary energy supply reduces infant mortality by 0.0139 PPs.

Food insecurity harms the health status of SSA countries, but food security impacts in the reverse direction. This implies that to meet SDG 3.2, SSA should ensure food security.

Food security is essential to people’s health and well-being [1]. Further, the World Health Organization (WHO) argues that health is wealth and poor health is an integral part of poverty; governments should actively seek to preserve their people’s lives and reduce the incidence of unnecessary mortality and avoidable illnesses [2]. However, lack of food is one of the factors which affect health outcomes. Concerning this, the Food Research and Action Center noted that the social determinants of health, such as poverty and food insecurity, are associated with some of the most severe and costly health problems in a nation [3].

According to the FAO, the International Fund for Agricultural Development (IFAD), and the World Food Programme (WFP), food insecurity is defined as "A situation that exists when people lack secure access to sufficient amounts of safe and nutritious food for normal growth and development and an active and healthy life" ([4]; p50). It is generally believed that food security and nutrition are crucial to improving human health and development. Studies show that millions of people live in food insecurity, which is one of the main risks to human health. Around one in four people globally (1.9 billion people) were moderately or severely food insecure in 2017 and the greatest numbers were in SSA and South Asia. Around 9.2% of the world's population was severely food insecure in 2018. Food insecurity is highest in SSA countries, where nearly one-third are defined as severely insecure [5]. Similarly, 11% (820 million) of the world's population was undernourished in 2018, and SSA countries still share a substantial amount [5]. Even though globally the number of people affected by hunger has been decreasing since 1990, in recent years (especially since 2015) the number of people living in food insecurity has increased. It will be a huge challenge to achieve the SDGs of zero hunger by 2030 [6]. FAO et al. [7] projected that one in four individuals in SSA were undernourished in 2017. Moreover, FAO et al. [8] found that, between 2014 and 2018, the prevalence of undernourishment worsened. Twenty percent of the continent's population, or 256 million people, are undernourished today, of which 239 million are in SSA. Hidden hunger is also one of the most severe types of malnutrition (micronutrient deficiencies). One in three persons suffers from inadequacies related to hidden hunger, which impacts two billion people worldwide [9]. Similarly, SSA has a high prevalence of hidden hunger [10, 11].

An important consequence of food insecurity is that around 9 million people die yearly worldwide due to hunger and hunger-related diseases. This is more than from Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome (AIDS), malaria, and tuberculosis combined [6]. Even though the hunger crisis affects many people of all genders and ages, children are particularly affected in Africa. There are too many malnourished children in Africa, and malnutrition is a major factor in the high infant mortality rates and causes physical and mental development delays and disorders in SSA [12]. According to UN statistics, chronic malnutrition globally accounts for 165 million stunted or underweight children. Around 75% of these kids are from SSA and South Asia. Forty percent of children in SSA are impacted. In SSA, about 3.2 million children under the age of five dies yearly, which is about half of all deaths in this age group worldwide. Malnutrition is responsible for almost one child under the age of five dying every two minutes worldwide. The child mortality rate in the SSA is among the highest in the world, about one in nine children pass away before the age of five [12].

In addition to the direct impact of food insecurity on health outcomes, it also indirectly contributes to disordered eating patterns, higher or lower blood cholesterol levels, lower serum albumin, lower hemoglobin, vitamin A levels, and poor physical and mental health [13,14,15]. Iodine, iron, and zinc deficiency are the most often identified micronutrient deficiencies across all age groups. A deficiency in vitamin A affects an estimated 190 million pre-schoolers and 19 million pregnant women [16]. Even though it is frequently noted that hidden hunger mostly affects pregnant women, children, and teenagers, it further affects people’s health at all stages of life [17].

With the above information, researchers and policymakers should focus on the issue of food insecurity and health status. The SDGs that were developed in 2015 intend to end hunger in 2030 as one of its primary targets. However, a growing number of people live with hunger and food insecurity, leading to millions of deaths. Hence, this study questioned what is the impact of food insecurity on people's health outcomes in SSA countries. In addition, despite the evidence implicating food insecurity and poor health status, there is a lack of macro-level empirical studies concerning the impact of food insecurity on people’s health status in SSA countries, which leads to a knowledge (literature) gap. Therefore, this study aims to examine the impact of food insecurity on life expectancy and infant mortality in SSA countries for the period ranging from 2001–2018 using panel mean regression approaches.

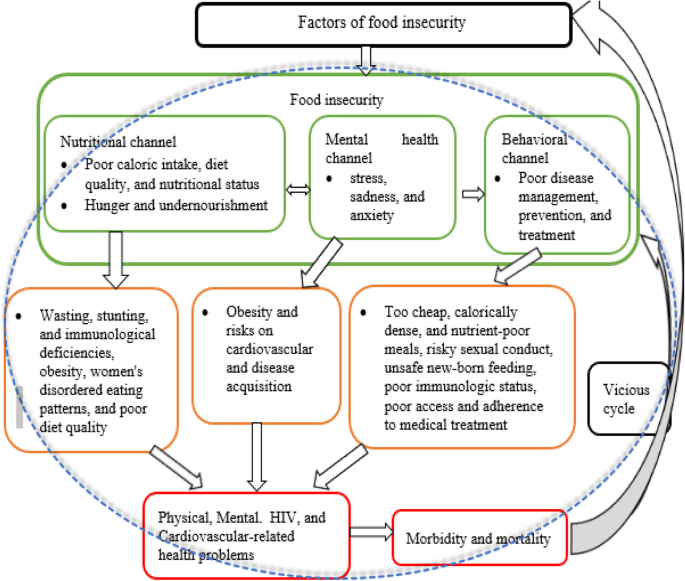

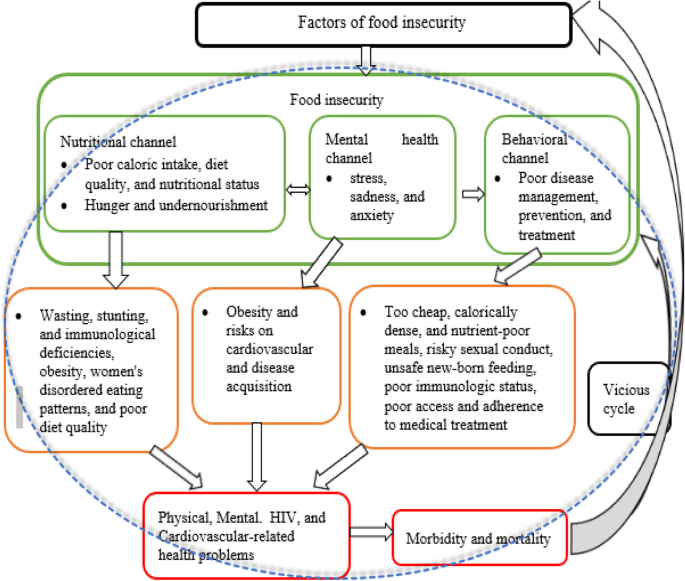

Structural factors, such as climate, socio-economic, social, and local food availability, affect people’s food security. People’s health condition is impacted by food insecurity through nutritional, mental health, and behavioral channels [18]. Under the nutritional channel, food insecurity has an impact on total caloric intake, diet quality, and nutritional status [19,20,21]. Hunger and undernutrition may develop when food supplies are scarce, and these conditions may potentially lead to wasting, stunting, and immunological deficiencies [22]. However, food insecurity also negatively influences health due to its effects on obesity, women's disordered eating patterns [23], and poor diet quality [24].

Under the mental health channel, Whitaker et al. [25] noted that food insecurity is related to poor mental health conditions (stress, sadness, and anxiety), which have also been linked to obesity and cardiovascular risk [26]. The effects of food insecurity on mental health can worsen the health of people who are already sick as well as lead to disease acquisition [18]. Similarly, the behavioral channel argues that there is a connection between food insecurity and health practices that impact disease management, prevention, and treatment. For example, lack of access to household food might force people to make bad decisions that may raise their risk of sickness, such as relying too heavily on cheap, calorically dense, nutrient-poor meals or participating in risky sexual conduct. In addition, food insecurity and other competing demands for survival are linked to poorer access and adherence to general medical treatment in low-income individuals once they become sick [27,28,29,30]

Food insecurity increases the likelihood of exposure to HIV and worsens the health of HIV-positive individuals [18]. Weiser et al. [31] found that food insecurity increases the likelihood of unsafe sexual activities, aggravating the spread of HIV. It can also raise the possibility of transmission through unsafe newborn feeding practices and worsening maternal health [32]. In addition, food insecurity has been linked to decreased antiretroviral adherence, declines in physical health status, worse immunologic status [33], decreased viral suppression [34, 35], increased incidence of serious illness [36], and increased mortality [37] among people living with HIV.

With the above theoretical relationship between target variables and since this study focuses on the impact of food insecurity on health outcomes, and not on the causes, it adopted the conceptual framework of Weiser et al. [18] and constructed Fig. 1.

Several findings associate food insecurity with poorer health, worse disease management, and a higher risk of premature mortality even though they used microdata. For instance, Stuff et al. [38] found that food insecurity is related to poor self-reported health status, obesity [39], abnormal blood lipids [40], a rise in diabetes [24, 40], increased gestational diabetes[41], increased perceived stress, depression and anxiety among women [25, 42], Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) acquisition risk [43,44,45], childhood stunting [46], poor health [47], mental health and behavioral problem [25, 48, 49].

The above highlight micro-level empirical studies, and since the scope of this study is macro-level, Table 1 provides only the existing macro-level empirical findings related to the current study.

Table 1 Empirical reviewEmpirical findings in Table 1 are a few, implying a limited number of macro-level level empirical findings. Even the existing macro-level studies have several limitations. For instance, most studies either employed conventional estimation techniques or overlooked basic econometric tests; thus, their results and policy implications may mislead policy implementers. Except for Hameed et al. [53], most studies’ data are either outdated or unbalanced; hence, their results and policy implications may not be valuable in the dynamic world and may not be accurate like balanced data. Besides, some studies used limited (one) sampled countries; however, few sampled countries and observations do not get the asymptotic properties of an estimator [56]. Therefore, this study tries to fill the existing gaps by employing robust estimation techniques with initial diagnostic and post-estimation tests, basic panel econometric tests and robustness checks, updated data, a large number of samples.

According to Smith and Meade [57], the highest rates of both food insecurity and severe food insecurity were found in Sub-Saharan Africa in 2017 (55 and 28%, respectively), followed by Latin America and the Caribbean (32 and 12%, respectively) and South Asia (30 and 13%). Similarly, SSA countries have worst health outcomes compared to other regions. For instance, in 2020, the region had the lowest life expectancy [58] and highest infant mortality [59]. Having the above information, this study's target population are SSA countries chosen purposively. However, even though SSA comprises 49 of Africa's 55 countries that are entirely or partially south of the Sahara Desert. This study is conducted for a sample of 31 SSA countries (Angola, Benin, Botswana, Burkina Faso, Cameroon, Cabo Verde, Chad, Congo Rep., Côte d'Ivoire, Ethiopia, Gabon, The Gambia, Ghana, Kenya, Lesotho, Liberia, Madagascar, Malawi, Mali, Mauritania, Mauritius, Mozambique, Namibia, Nigeria, Rwanda, Senegal, Sierra Leone, South Africa, Sudan, Tanzania, and Togo). The sampled countries are selected based on data accessibility for each variable included in the empirical models from 2001 to 2018. Since SSA countries suffer from food insecurity and related health problems, this study believes the sampled countries are appropriate and represent the region. Moreover, since this study included a large sample size, it improves the estimator’s precision.

This study uses secondary data collected in December 2020 online from the databases of the Food and Agricultural Organization (FAO), the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), and the World Bank (WB) (see Table 2). In addition, the study uses yearly balanced data from 2001 to 2018, which is appropriate because it captures the Millennium Development Goals, SDGs, and other economic conditions, such as the rise of SSA countries’ economies and the global financial crisis of the 2000s. Therefore, this study considers various global development programs and events. Generally, the scope of this study (sampled countries and time) is sufficient to represent SSA countries. In other words, the study has n*T = 558 observations, which fulfills the large sample size criteria recommended by Kennedy [56].

Table 2 Data type, sources, and measurementsModel specification is vital to conduct basic panel data econometric tests and estimate the relationship of target variables. Besides social factors, the study includes economic factors determining people's health status. Moreover, it uses two proxies indicators to measure both food insecurity and health status; hence, it specifies the general model as follows:

$$\overbraceThe study uses four models to analyze the impact of food insecurity on health outcomes.